The predictable Japanification of U.S. corporates

By JENNA BARNARD/Guest Contributor

In an article we published in early March, I wrote “When we do come out of the coronavirus ‘recession’ we will be in a world of ‘zero interest’ rates across the developed world; central banks buying even more investment grade corporate bonds via quantitative easing, a stumble towards fiscal stimulus and a cleansing of the ‘value’ areas of the credit markets that have been zombies for years (high yield energy being the most obvious example). As a result, I would not be surprised to see even lower yields on quality corporate bonds by the end of the year than where we started.”

This view was rooted in the experience of the European and UK corporate bond markets in recent years and follows the experience of Japan decades ago. ‘Japanification’ is a loose term to explain the fact that many of the challenges that face economies of the developed world today were first present in Japan twenty years ago. As weak growth, ever‑lower interest rates and negative bond yields have spread to the rest of the world, Japan has become the lens through which markets view these economies.

Japanification spreads to the developed world

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks, regulators, and policymakers were forced to take extraordinary measures to prop up their economies. Despite their efforts, growth and inflation remained stubbornly low in the developed world, while the extended period of accommodative policy resulted in ever decreasing interest rates and bond yields, at times into negative territory (Europe), with the US remaining an exception. Falling government bond yields and interest rates over the last few years were to us clear indications of the Japanification of Europe.

We have long spoken of the failure of mainstream economics, which has repeatedly over‑forecast growth and inflation in the developed world and looked to focus on long‑term thematic factors which weigh down bond yields such as demographics, excess debt and the impact of technology. As a result, between 2014-18, most countries in the developed world only cut interest rates. North America was an exception with the Bank of Canada and US Federal Reserve (Fed) pushing on with modest interest rate hiking cycles. This interest rate divergence had already come to an end with modest rate cuts from the Fed in 2019 and was accelerated in 2020 as a result of the pandemic. The significant emergency measures taken by major central banks to combat the crisis, and the Fed in particular, slashed government bond yields in the US and elsewhere. As government bond yields declined further, investors looked to the corporate bond markets, specifically in the US.

The Japanification of volatility

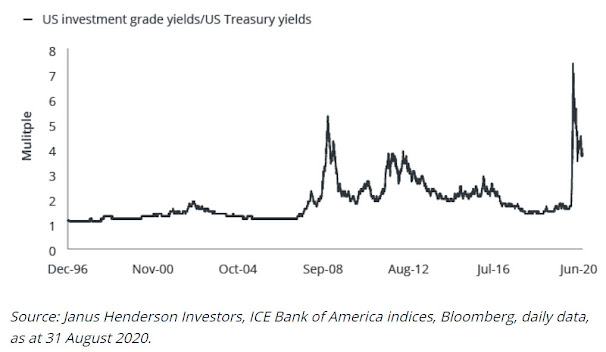

Similar to the experience in Japan, in the COVID‑19 crisis central banks succeeded in suppressing volatility through various extraordinary stimulus measures. Thus, policymakers dampened interest rate volatility and reduced systemic risk, creating an idyllic environment for investing in corporate bonds.

In the US, the Fed’s programs of support for investment grade and, to a lesser extent, some high yield default risk (through purchases of high yield exchange traded funds) further dampened volatility in the bond markets. The result was predictable enough: for investors in need of income, the exceptionally low and stable government bond yields made investment grade bonds an attractive alternative.

Exhibit 1A: Investment Grade Corporate Bond Yields’ Multiple Over US Treasury Yields

|

| Click graph to enlarge. |

The era of ‘new sovereigns’

According to a research paper by Bank of America, around two‑thirds of the global fixed income markets currently yield less than 1%. European sovereign bond yields fell dramatically in the years post the GFC, and in 2010-11, when the yield on 5‑year bunds fell below 1%, bond investors rotated out of government bonds into the credit markets. Similar to the experience in Europe, the US corporate bond market has seen increased demand and large inflows of capital in recent months. Catalyzed by the actions of the Fed, the primary market (issuance market) for US corporate bonds reopened quickly in the crisis. Borrowers took advantage of the lower borrowing costs to procure sufficient funds for their operations in the difficult months ahead and/or extend the maturity of their debt by selling longer- and longer‑dated bonds to yield hungry investors. With low levels of inventories for trading in the secondary market, demand for new issues has been huge in the primary bond market with many deals oversubscribed, despite a record‑breaking pace of supply ($1.4 billion in investment grade issuance through to September 8, compared to $0.8 billion for the whole of 2019).

Exhibit 1B: Floodgates Opened for Investment Grade Issues in March

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

Flows into the investment grade and high yield markets have continued well into August. They have been further boosted by a resurgence in overseas buyers, given that the cost of hedging back to local currencies have come down with the decline in interest rates.

Interestingly, given the paltry returns on government bonds, investment grade corporate bonds have now become the alternative source for potentially 'safe' yield. Thus, well‑known, quality, ‘sensible income’ generating companies are almost the new sovereigns.

Lower volatility is a boon for corporate bond markets

Lower volatility helps to improve the risk/return profile for fixed income assets despite lower yields. In Japan, corporate bonds have, perversely, delivered solid risk‑adjusted returns over the years, despite offering relatively lower yields and credit spreads. A historical analysis by Bank of America has shown that over the past two decades, Japanese investment grade corporate bonds, with an average credit spread of around a quarter to one‑fifth of their equivalents in Europe and the US, have delivered a much higher risk‑adjusted return, helped by the tailwind of lower volatility.

So long as central banks can maintain a credible commitment to low interest rates for years to come, this idyllic environment can continue as it has done in other countries. However, US 10‑year sovereign bond yields now look about 50 basis points too low relative to our models of the rate of change of economic data. The ‘easy money’ has been made in investment grade corporate bonds as the predictable Japanification theme has played out in months, rather than years.

Janus Henderson Investors is an Associate member of TEXPERS. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily Janus Henderson nor TEXPERS.

About the Author

Jenna Barnard is Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income at Janus Henderson Investors, a position she has held since 2015. She manages and co-manages a range of strategic fixed income strategies and funds meeting different client needs globally. Barnard joined Henderson in 2002 as a credit analyst and was promoted to portfolio manager in 2004. Prior to this, she worked as an investment analyst with Orbitex Investments. She graduated with a first class BA degree (Hons) in politics, philosophy and economics from Oxford University. She holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation, is a member of the Society of Technical Analysts and is an Affiliate Member of the UK Society of Investment Professionals. She has 19 years of financial industry experience.

Follow TEXPERS on Facebook and Twitter and visit its website for the latest news about the public pension industry in Texas.

No comments:

Post a Comment