|

| Photo by Daniel Joseph Petty from Pexels. |

By ALLEN JONES/TEXPERS COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

A new research paper suggests design changes for U.S. public pension plans based on the Canadian system, which is touted as a recognized “global gold standard” of pension management.

The paper, Public Pension Reform and the 49th Parallel: Lessons from Canada for the U.S., released July 8, traces the history of the “Canadian Model,” highlighting its reforms during the late 1980s and the 1990s, and how it became well regarded in pension management. Researchers from the Stern School of Business at New York University then compare the Canadian Model with 25 of the largest public pension systems in the U.S., including the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

> READ MORE: The paper's authors wrote an article for Institutional Investor.

> LEARN MORE: Find out what NASRA has to say about pension reform.

The paper’s authors, Clive Lipshitz and Ingo Walter, say there is a growing attention on the long-term sustainability of many U.S. pension funds along with concerns of equity between pension plan members, retirees, taxpayers, bondholders, and public services consumers. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is introducing “new fissures in state and local government finances, heightening the need to bolster long-term public pension fund robustness,” write the researchers. The Canadian public pension system, they write, may hold the key to sound reform.

“It is widely accepted that the Canadian public pension system functions well, with enviable funding levels,” write Lipshitz and Walter. “Indeed, the so-called ‘Canadian Model’ of pension management is often seen as a global gold standard in the realm of public finance.”

Even now, according to Fitch Ratings Inc., Canada’s 11 largest pension funds should maintain their current credit ratings despite the ongoing market turmoil. The funds managed 1.7 trillion of net assets in Canadian dollars at year-end 2019. In a July 7 report on its website, Fitch Ratings indicates the Canadian plans are expected to “withstand market downturns within their respective ratings given their long-term investment horizons, ability to adjust contribution rates and the captive nature of inflows.”

The Canadian Model wasn’t always seen in such favorable light. The Stern School of Business researchers say that in the early 1990s, the Canadian pension system’s various provincial public pension plans were financially challenged.

“Their subsequent successes were hardly inevitable or predictable at the time,” write the authors. “[The Canada Pension Plan – comparable with U.S. Social Security] was structured as a pay-as-you-go system and many of the provincial plans were funded through superannuation accounts. They were not independent of government and invested largely in Canadian sovereign and provincial debt.”

Conducting a side-by-side analysis of primary data sources of key plan features in both countries, in their report, the researchers outline key changes undertaken in Canada in the late 1980s and during the 1990s. The changes resulted in positive reforms on Canadian public pension funds comparative to those in the U.S., write the researchers.

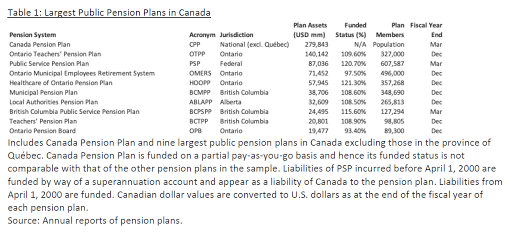

Their report compares data sourced directly from public filings of the 25 largest public pension systems in the U.S. and nine of the largest public pension plans in Canada as well as the Canada Pension Plan. The paper’s dataset is sourced from 11 years of annual reports for the 35 pension plans, ending in 2018.

According to the paper, global commodity markets had led to cyclical pressures on the economy throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Debt among the federal and provincial Canadian pension systems grew, highlighting key pension plan design flaws:

- Plan funding was partially on a pay-as-you-go basis or through superannuation accounts

- Enhancement to benefit levels were retroactive and not matched with higher contribution rates

- Contributions were commingled with general government funds rather than funded into segregated accounts

- Active portfolio management was nonexistent

- Plans were defined in law that determined contribution rates by political processes and required legislative action to modify

- Because plans were sponsored by the government, beneficiaries were unable to influence plan design and lacked responsibility for ensuring plan solvency.

Between the late 1980s and the late 1990s, a series of reforms addressed these issues. Even though particulars of plans differ from province to province, common features characterize the Canadian Model. These include joint sponsorship – giving labor the ability to make decisions – and independently governed and professionally managed organizations to invest pension reserves. According to the paper’s authors, optimal governance prioritizes the interests of principals (active and annuitant plan members, taxpayers, municipal bondholders, and users of government services) over those of agents (trustees, government officials, and union representatives) and agents of agents (actuaries, fund managers, lawyers, and consultants).

“It is the principals who should determine plan features and play a central role in plan governance,” write the researchers. “A new governance model was established in Canada, framed on joint sponsorship and governance, independence form government, uniformity in legislation and regulation, and minimum standards of professionalism on pension boards.”

The 56-page report compares the largest pension plans in Canada and the U.S., looking at demography; plan design; plan benefits and risk sharing; discount rates; funded status; investment organization; primate market and direct investing; size effects; the consortium model; investment strategy; asset allocation; portfolio leverage, derivatives and currency hedging; and investment performance.

The lessons gained from Canada’s reform and comparison of the two countries, according to the researchers, address what is becoming a critical public finance challenge in the U.S. The report identifies 15 policy initiatives:

- Recognize the need for change. Outside factors, such as the current economic environment, are a catalyst for change.

- Solution needs to be at the appropriate level of government. Change should occur at least at the state level.

- Change requires strong leadership and effective civil service. Strong leaders must operate in each state, require the support of skilled professionals, and enable forums for sharing knowledge between jurisdictions.

- Adopt a consultative stakeholder approach to develop and implement reforms. Involve all parties in the reform process, including taxpayers, bondholders, and recipients of government services – not just plan members and retirees.

- Focus on holistic models for pension design and funding. Restructure funding models to focus on solvency rather than have benefits, contributions, and investing determined distinctly; remove plan terms from collective bargaining.

- Share burden of funding contributions more equitably. Understand pension funding within the framework of total compensation and consider a more equitable share of funding from plan members.

- Mandate sponsor funding. Hold governments accountable for funding of contributions.

- Align benefits and responsibilities through joint sponsorship. Construct a plan where members can make decisions and accept a shared risk for solvency.

- Enhance governance. Enact high standards for trustees and trustee education.

- Unify legislation. Utilize any existing tools for creating unified pension legislation and reconsider the possibility of setting national standards.

- Ensure viable model for funding accumulated deficits. Amortize unfunded liabilities using combination of sponsor funding and plan member contributions.

- Align investment strategies to liabilities and cash flows. Once plans are better funded, match asset allocation to liability management.

- Internalize investment management, where appropriate. Evaluate ability to address governance and compensation constraints to facilitate direct investing approach.

- Evaluate consortium model to achieve scale, where appropriate. Consider establishing consolidated investment management for groups of pension plans to achieve scale and reduce expenses.

- Enhance advisor standards. Enhance expectations for service providers as internal resources and governance are improved.

About the Author:

No comments:

Post a Comment