Thursday, February 25, 2021

Monday, December 21, 2020

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Sportswear: Sweet Success Amid COVID-19?

As a discretionary good, sportswear may seem an unlikely

winner in the wake of COVID-19. But the category—which includes athletic

apparel and footwear—has some unique characteristics that make us think it will

emerge just fine. In fact, for stronger companies, we believe COVID-19 will be

an accelerant as the companies leverage their connections with consumers and

drive business through more profitable channels.

A Long Runway for Growth

The total addressable market (TAM) in the sportswear space is estimated at $472 billion globally.

WHAT IT MEANS: Total addressable market is a term that is typically used to reference the revenue opportunity available for a product or service.

At William Blair Investment Management, while apparel and footwear is a low-growth category overall, we have seen sportswear take increasing share over time. Sportswear increased from about 18% of the apparel category in 2007 to almost 26% in 2019.

In fact, sportswear has shown a 6.5% compound annual

growth rate (CAGR) over the past five years, one-and-a-half times that of the

apparel market

We believe this trend will continue, driven in part by a

growing middle class around the world. Per capita sportswear spending in

emerging markets, particularly China, is one-tenth that of the United States,

and has plenty of room to grow.

Economic Cycles: Mostly Background Noise

The sector’s behavior in response to economic cycles has

been mixed. While there is an impact from the economic backdrop, there are many

times that results have been detached from the economic cycle.

For example, sportswear growth peaked in 1995 and

decelerated through 1999, leading the stocks to underperform the broader

market. After bottoming in 1999, sportswear started a five-year growth

acceleration, leading to strong stock performance.

This is exactly the opposite of what the broader market

was doing: The market peaked in 2000, and growth slowed as the U.S. economy

went into a recession in March 2001.

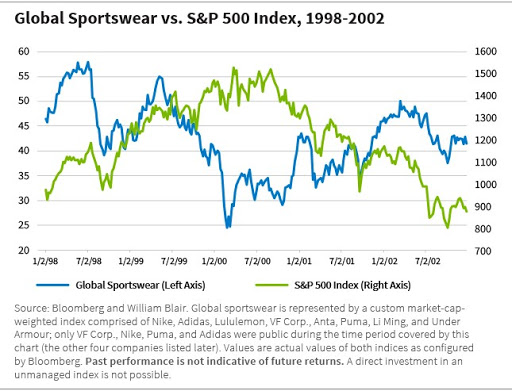

As the chart below shows, the S&P 500 Index peaked at

roughly the same time sportswear bottomed, presenting a prominent case for how

sportswear performance has detached from the economic backdrop at times.

WHAT IT MEANS: The S&P 500 is a stock market index that measures the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the U.S.

This was also apparent after the 9/11 attacks,

where we saw sportswear quickly recover despite continued weakness in the

broader market.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

We saw more economic sensitivity

during the global financial crisis (GFC). Both the S&P 500 Index and

sportswear companies peaked around the same time, within two to three months of

each other.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

However, sportswear fundamentals

were fairly resilient. Revenues across the group declined 3% in 2009 and

earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) were down 35%, but there was a strong

rebound in 2010. While sportswear fundamentals recovered within five to seven

quarters, sportswear stocks surpassed prior peaks within a year of

bottoming—much faster than the market, due to clear visibility and robust

growth.

The key takeaway: economic cycles

matter, but they have not been as impactful as we might think they would be. We

are seeing a number of sportswear companies perform outside of the economic

cycle.

Product Cycles: Critical in the Near and Medium Term

To understand the sportswear

space, one must appreciate product cycles. While sportswear companies are not

high-fashion companies, there is a fashion element to their success, and they

need to remain on trend.

WHAT IT MEANS: A product cycle is the length of time a product is introduced to consumers into the market until it's removed from the shelves

The chart below illustrates how

three key sportswear companies performed in past product cycles.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

A running-related product cycle

started in the mid-2000s. It was interrupted somewhat by the GFC, but then came

back with a vengeance. This is when we saw the Nike Free and Vibram Five

Fingers products take off.

Sportswear Company 1 in the chart

above was well positioned for this cycle; Sportswear Company 3 was not. As a

result, Sportswear Company 1 outperformed Sportswear Company 3 significantly

from 2012 to 2015.

Then, from 2015 to 2018, retro

sportswear came into fashion. Sportswear Company 1 continued to push the

running platform while Sportswear Company 3 was on trend for retro. Guess which

outperformed?

We are now in a new product cycle

that we call high fashion and collaborations. Brands are collaborating with

different designers and luxury houses (Kanye West, Selena Gomez, Beyoncé, Dior,

and Off-White to name just a few), and new product releases are coming out

monthly if not weekly. Most leading brands are participating successfully in

this trend.

There are two key takeaways.

First, the category has a degree of fashion risk (such as the move away from

technical performance and athletic functionality), although it is less

pronounced than in luxury or casual wear.

Second, once we identify companies

that we believe have strong brand equity and solid management teams, we need to

make sure we are patient, because even the best will potentially miss a trend

and have a period of underperformance relative to peers.

Investment Opportunities

Over time we have seen brands

rationalize their supply chains, allocating more orders to what we would call

key manufacturing partners. We view key suppliers as strategic partners and

more akin to internal manufacturing than external. A single supplier, for

example, manufactures about one-sixth of Nike’s shoes globally.

We also see this happening on the

distribution side. Brands are culling undifferentiated wholesalers and

diverting more in-demand products to strategic retail partners. We view these

retail partners as part of a brand’s direct-to-consumer efforts more than

wholesale.

The return on invested capital

(ROIC) for these strategic partners is typically fairly robust and at times has

exceeded the brands’ ROIC, indicating that there is substantial value creation

throughout the entire value chain.

WHAT IT MEANS: Return on invested capital is a calculation used to assess a company's efficiency at allocating the capital under its control to profitable investments. The return on invested capital ratio gives a sense of how well a company uses its money to generate profits.

On that note, we see a long runway

for brands to shift sales from the wholesale channel (70% of Nike’s and

Adidas’s business) to the direct-to-consumer (DTC) channel, which includes

their own retail footprints and e-commerce operations.

WHAT IT MEANS: Direct-to-consumer is the selling of products directly to customers, bypassing any third-party retailers, wholesalers, or any other middlemen.

We believe the big brands have the

potential to reach about 50% DTC penetration in the next 10 years, and perhaps

even higher over the long term. Some estimates place DTC at 70% of the sales

mix.

While brands do not provide the

profitability difference between the two channels, we estimate that DTC

generates double the revenue and EBIT dollars of wholesale, underscoring just

how accretive the mix shift from wholesale to DTC is.

WHAT IT MEANS: EBIT stands for earnings before interest and taxes, and is a company's net income before income tax expense and interest expenses are deducted.

Sportswear in the Wake of COVID-19

We have long identified health and wellness as a structural theme driven by consumers being increasingly concerned by the connection between their lifestyle (physical activity and food consumption) and their overall health.

COVID-19 and the potential health

risks have intensified the desire to eat better, live better, and feel better.

We believe sportswear is well positioned to benefit from this as consumers

express this desire through active lifestyles.

While we believe the long-term

view for sportswear remains positive, COVID-19 has presented an unprecedented

situation resulting in a coordinated global retail shutdown. The ensuing

consumer weakness (such as unemployment), combined with a broader apparel and

footwear inventory glut, will likely hurt discretionary spending overall.

This will undoubtedly depress

near-term sales and margins as sportswear companies adjust to overall market

conditions.

Despite these challenges,

sportswear appears to be a resilient category in the midst of COVID-19, and not

just because the pandemic appears to have intensified consumers’ desire to

focus on their health and wellness.

Sportswear companies, over the

past few years, have woven digital engagement into their DNA. Their ability to

speak directly to an audience without a physical footprint, amplify their

messaging, and drive engagement has allowed them to drastically accelerate

online sales during the lockdown.

Multiple brands, for example, have

reported triple-digit e-commerce growth in China throughout the lockdown,

helping them offset lost brick-and-mortar retail sales.

While the pace of the recovery

varies by brand and region, we are encouraged by what we are seeing and

anticipate that sportswear sales will be one of the fastest discretionary

categories to recover, as we have seen in prior downturns. As retail conditions

normalize globally, so will sportswear sales.

After all, the category has a long track record of value creation over the past 30 years. We have every reason to believe this will continue over the long term.

Friday, June 21, 2019

BY BLAKE S. PONTIUS, William Blair Investment Management

The January 2019 collapse of a Brazilian mine tailings dam—which released 11.7 million cubic meters of toxic mud, killed at least 150 people, and led to a corruption probe—underscores the critical but underappreciated value of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations in emerging markets.

ESG: More Important in Emerging Markets?

The majority of ESG-aware asset managers surveyed by Citi Research in October 2018 expressed the view that ESG factors are more important in emerging markets than developed markets, particularly from a corporate governance risk perspective.Generally, weaker corporate governance practices in emerging markets relative to developed markets have played a role in shaping this opinion. More seasoned, quality-focused investors have long appreciated the need to be sharp on governance considerations when investing in frontier countries such as Kenya and Argentina, as well as the more mainstream countries such as China, India, and Brazil.

We’ve seen a variety of environmental and social issues become increasingly relevant to investors.

Emerging markets have more state-owned enterprises, necessitating a higher level of scrutiny of governance practices by prospective investors. While varying across different countries, there is generally a greater prevalence of family founders with majority stakes within emerging markets. Lower rates of board director independence and weaker corporate transparency are other realities contributing to the elevated governance risk profile.

Beyond these more obvious considerations related to governance and business culture, we’ve seen a variety of environmental and social issues become increasingly relevant to investors. From an environmental perspective, combating air, soil, and water pollution is becoming a more significant focus of government policy in China and India. And from a social perspective, investors are increasingly scrutinizing how companies are managing broader stakeholder relationships that can materially impact financial performance.

Back to the Brazilian Dam Disaster

The latter point takes us back to the Brazilian dam disaster.The resource-intensive energy and materials sectors continue to play an important role in the socioeconomic welfare of many emerging and frontier economies, with concomitant ESG risk factors that can have severe consequences beyond share price performance.

For example, mining companies that operate in environmentally sensitive areas where indigenous populations live have to be thoughtful about how they develop resources. They must also ensure the safety of their employees through ongoing capital investments and training.

Brazil’s Vale SA, which owns the dam that collapsed in Brumadinho, knows that all too well. The company has since announced that it will close all 10 of its dams in the country with a similar design.

Ratings Reflect Greater Risks, but also Opportunities

These risks can be seen in the ESG ratings distributions of emerging versus developed markets. Conventional ratings distributions, such as the one shown below from MSCI, reflect a negative skew in emerging markets relative to developed markets. (Applying MSCI’s ratings methodology, CCC is the lowest ESG rating assigned to companies on an industry-relative basis and AAA is the best.) |

| Click graph to enlarge. |

This negative skew in ESG ratings reflects some of the risks I discussed above, with a consistent overhang being weaker governance structures for companies across different sectors within emerging markets. Companies lacking a majority independent board, for example, are systematically penalized. The existence of a combined chairman and CEO or dual share classes with unequal voting rights are also detrimental to the rating.

Over time, we expect ESG ratings for emerging market companies to broadly improve as more capital flows into ESG-focused equity and fixed-income strategies, and as more asset managers integrate ESG considerations in traditional strategies.

Emerging market ESG funds now account for nearly 10% of global emerging markets funds, up from just 2% a decade ago, as illustrated below.

Growth of ESG Assets in Emerging Markets

We’ve already seen tremendous growth in ESG-focused emerging markets fund assets, from less than $1 billion in 2008 to $20 billion in 2018, as measured by EPFR and Citi Research. Emerging market ESG funds now account for nearly 10% of global emerging markets funds, up from just 2% a decade ago, as illustrated below.Asia ex-Japan represents a significant percentage of ESG-focused assets in emerging markets based on data collected by the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), with the largest markets for sustainable investing being Malaysia (30% of total professionally managed assets), Hong Kong (26%), South Korea (14%), and China (14%).

Malaysia’s prominence may come as a surprise considering the high-profile scandal involving its state-owned investment fund, 1MDB. Similarly, China’s inclusion on the list of prominent ESG markets contradicts the conventional perception of weaker governance given the role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and environmental mismanagement (ambient air pollution kills hundreds of thousands of citizens every year, according to the Chinese Ministry of Health).

But, perhaps surprisingly, according to a recent biannual review of corporate governance practices in Asia by research firm CLSA, Malaysia was the “biggest mover in 2018,” climbing to 4th place in Asia’s corporate governance market ranking.

And China was the fastest-growing market for sustainable investing from 2014 to 2016, according to the GSIA. Sustainable assets there were up 105%, followed closely by India (up 104%).

Much of that growth was driven by investment opportunities arising from public policy initiatives to clean up the environment, including China’s efforts to improve air quality by working to transition away from coal toward natural gas and renewables.

About the Author: