Thursday, October 29, 2020

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

It is not too late to de-FAANG your portfolio

|

| Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay |

If the only alternative to forecasting ability is accessing the risk premium in its purest form, some investors in their search for the beta believe that passive management, defined as the investment vehicles tracking market-capitalization weighted indices, offers access to this beta. There is a myth or misunderstanding that “passive = neutral”.

The shortcomings of replicating market-cap weighted benchmarks

Passive investing, which is often described as beta investing, does not provide neutral access to the risk premium. Investing in a cap-weighted benchmark means buying a portfolio that can be hugely biased to sectors, styles, countries and individual securities. There is ample academic literature to support this.

These benchmarks take on heavy structural biases that evolve over time. They are inherently biased as they attribute greater index representation to stocks or factors as they have appreciated and less after they became cheaper. They represent the sum of all speculations of all market participants and these implicit bets change dynamically over time as the benchmark re-weights assets. Because they attribute greater representation to stocks whose share prices have risen, market capitalization-weighted benchmarks maximize their exposure to the past winners.

As a consequence, they do not offer pure beta or immunity from financial speculation.

Furthermore, because an investor tracking these indices would therefore have to allocate more money to the largest risk drivers, these benchmarks inherently forecast that the successes of the past will be successes of the future.

Chart 1: US Equity Market - Sector Weights

For investors seeking diversification both within and among broad investment universes using market cap weighted indices such as MSCI US or MSCI Emerging Markets, they may be surprised to learn that these indices today reflect historically high levels of risk concentrations in a few stocks with large weights and whose price movements have increasingly been moving in similar directions.

When it comes to diversification, investors may tend to consider spreading investments out across many securities, sectors, regions, and asset classes. That’s only part of the story; a portfolio is well-diversified if its holdings avoid sharing common, correlated risk.

Examining the current level of diversification in Equity markets

As some investors consider weights as an appropriate measure of exposure, we will examine first the collective weights of the top 5 stocks in US and Emerging Markets equities as of end July:

Chart 2: MSCI USA Universe

Weight Concentration: Top 5 Stocks = Bottom 431

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

Not only is the weight concentration of these leaders in Developed and Emerging Markets indices very high as a proportion of the investable universe, but ….

Chart 3: MSCI EM Universe

Top Weight Concentration: Top 5 Stocks = Bottom 1112

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

Chart 4: Relationships Between the Top 5 Stocks in Both S&P 500 and MSCI EM:

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

…. these charts also show that investing in US or Emerging Equities via passive ETFs is providing very similar exposure as investing in the FAAMG companies and their partners, competitors, providers, all surfing on the same wave.

TOBAM introduced and patented the Diversification Ratio which aims to measure to what extent a portfolio is diversified. Using this measure, we can demonstrate that the overall level of diversification available in these universes is currently at historical lows last observed in 2002. This ratio has been steadily declining in the MSCI US index since December 2014 and since September 2016 in the MSCI EM index, exposing passive investors to a limited number of independent risk factors and thus depriving them of broad, diversified exposures.

Chart 5: MSCI US Universe DR²

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

Chart 6: MSCI EM Universe DR²

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

The currently historically low levels of the Diversification Ratios for MSCI US and MSCI EM indices suggests that investors using ETFs tracking these indices are leaving a lot of diversification on the table. Even worse so, the tech outperformance during the recent market turmoil made US markets even more concentrated.

At the same time, the first clouds arrive on the skies of the big tech companies in EM markets. The underperformance of the EM tech mega caps in the rebound contributed to a slight de-concentration. Is this the beginning of a longer-term trend?

How to invest during a historically high market concentration, along with high economic and political uncertainty?

Given the recent rise in turbulence in equity and bond markets, investors may feel their crystal ball is cloudier than in the past, in fact, in fact, how realistic is the expectation of having a clear and concrete picture of the true economic impact of the coronavirus crisis? After all, the future evolution of the virus spread is, itself, completely unclear. On that basis, how can investors know what even central banks and governments do not?

So, what comes next? As a second phase of the market slump, will signs of a massive consumer crisis become non negligible and be priced into sectors or stocks that have seemed almost invulnerable so far such as the FAAMG? Will a second (or, indeed, third) wave of virus infections send us all back into a lockdown with almost unquantifiable further economic consequences? And for how long can central banks and governments credibly continue to play the white knight?

All what that we know at this point is that we know nothing for certain. The best answer to such uncertainty and a future that we cannot forecast is, most likely, the principle of diversification.

Looking back, a well-diversified portfolio would have prevented investors from being overly exposed to the oil price shock and the massive sector sell-off, while allowing the average investor to take advantage of the true market risk premium in an environment of highly dispersed asset prices. While the art of constructing of a truly diversified portfolio would be worthwhile an article by itself, there is no uncertainty that these basic laws of portfolio construction will continue to be applicable and deliver the true market premium to investors.

TOBAM Core Investments is an Associate Member of TEXPERS. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily TOBAM nor TEXPERS.

About the Author

Tatjana Puhan, is Managing Director, Deputy Chief Investment Officer at TOBAM. She is responsible for the management of all research and product creation related projects, Co-Management of the Research and Portfolio Management as well as Trading teams based in Paris and Dublin assuring the coherence and application of the investment process. Previous to joining TOBAM, Puhan was appointed as Head of Equity and Asset Allocation for Third Party Asset Management at Swiss Life Asset Managers. In this role, she was responsible for a number of the company’s flagship strategies, most notably its investment solutions utilising systematic and proprietary quantitative approaches, as well as contributing to Swiss Life Asset Managers’ asset allocation and equity research initiatives. Puhan has more than 15 years’ investment experience, worked at a number of leading asset management and private banking businesses while also bringing a strong academic and research background.

Puhan holds a Master’s degree in Finance and Business Administration from the University of Hamburg, and gained her Ph.D. in Finance from the Swiss Financial Institute at the University of Zurich, with research fellow appointments at the University of Zurich, Kellogg Business School (Northwestern University) and the University of Hamburg. She is a lecturer in finance at the University of Mannheim and an associated researcher of the Hamburg Financial Research Center.

Risk Mitigation Opportunities: Taking Time to Re-evaluate Portfolio Strategies and Board Governance

|

| Image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay |

The traditional 60% S&P 500 - 40% Aggregate Bond index investment portfolio has been the benchmark for portfolio construction for decades due to the inverse return relationship between equities and fixed income and higher historical bond yields. This simplistic mix had provided returns for pensions that allowed them to meet their actuary assumed returns. The S&P 500 index posted an approximate annualized average return of 11.3% for the past 10 years (ending 2019)[1], while the current yield on the Aggregate Bond Index less than 1.5% (coupon rate of hovering around 3%). The correlation between the two indexes has been slightly negative for the past ten years, and bonds have not provided a consistent offset for drawdowns within the S&P 500 index. Over the next five years, earning a 5% annualized return will be tough. Based on recent comments from the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the expectation for higher interest rates in the intermediate term is minimal. While investors cannot control what the Fed is doing, we can recalibrate current positioning and take a serious look at the risk within the portfolio and its governance.

Investment Strategy

The first question that most investors have started to ask themselves is how to replace the missing yield from the fixed income market. When seeking a replacement, many forget to fully vet the additional risks associated with finding an alternative. While there might be other public and private options, each one brings a different type of risk profile to the portfolio, which must be considered. Hence, swapping one investment for another is a naïve approach that could have detrimental effects if the understanding of current and potential strategies is vague. This is an important area to focus on, and what an investment advisor is paid to do. You might have a relationship with an advisory firm in which they present you with options or a fiduciary that does the decision-making and portfolio construction for you. In either case, this is the time for an investment committee to focus on oversight elements that are usually glazed over. From an investment perspective, members should take this time to:

- Re-evaluate their Strategic Allocation

- Update their Investment Policy

- Refresh their Objectives

- Evaluate their tactics around allocation of assets and assessment of those decisions

- Revisiting their Spending Policy

- Gauging the overall risk of their exposure

- Homing in on their underlying market exposures to events that could be detrimental to returns

- Measuring the volatility of returns for each fund and portfolio as a whole

- Considering drawdown of the portfolio

Governance Structure

Understanding and addressing the potential holes within the governance of a board is equally important to understanding current market conditions. Unfortunately, this rarely gets the same attention as the latest news from the stock market does.

As investment professionals, we spend far too much time talking about the markets, but clients’ governance structure usually has glaring holes and creates just as much risk for plans. The adoption of good governance starts with:

- Addressing educational needs within the board

- Introduction of term limits

- Staggering board terms

- Independent, third-party reviews of board investment process

- Proactively minimizing conflicts of interest

- Re-evaluate current investment advisor beyond investment performance

- Utilizing board assessments

It is crucial for boards to maintain discipline in their governance and review processes; while it may not seem as exciting as stock and fixed income movements, it is equally as important of an exercise for more efficient portfolio management.

PFM is an Associate Member of TEXPERS. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily PFM nor TEXPERS.

Sources

[1] Bloomberg

About the Authors

Floyd Simpson III, CFA, CFP, is Senior Managing Consultant with PFM Asset Management LLC. As part of PFM’s OCIO business, Simpson works with clients across the country to develop and implement multi-asset class strategies for their portfolios. He also serves on the Multi-Asset Strategies Group and the Multi-Asset Class Investment Committee.

Mallory Sampson, CFP, is Senior Managing Consultant with PFM Asset Management LLC. Sampson manages PFM’s institutional multi-asset class relationships in Texas, with a focus on higher education, endowments, foundations and OPEB trusts.

Monday, August 24, 2020

Recessions and Factor Performance: What History Tells Us

|

| Image by Mediamodifier from Pixabay |

It’s official. On June 8, 2020, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declared that the United States entered a recession in February of this year. Somewhat anomalously, after falling roughly 33% from its high to usher in a bear market, the S&P 500 Index had rallied nearly 45% from its lows on March 23 through the date of NBER’s recession announcement.

So while it is bad times for the economy, the stock market has regained some of its former euphoria. Investors may be wondering what this means for stocks going forward, and for the investment factors that shape stock returns.

We can’t predict the future—but we can examine history. Our research into how factors performed before, during, and after previous recessions confirms that it’s risky for investors to try to time economic cycles and factor performance.

The Data on Factor Returns and Recessions

The chart below shows the average monthly returns for the Fama-French factors and momentum in a variety of economic environments. The data goes back to July 1926 and includes 15 recessions. The current recession is excluded as it has yet to run its full course.

As we see in the chart’s top row, all factors have positive returns when invested over the long term. Performance differences first appear when we look at returns during economic expansions and recessions[1]. During expansions, all factors are again nicely positive and are statistically and economically significant. The story is somewhat different when we look at recessions: Both the market’s excess return and small size returns are now negative, and value returns are notably reduced.

These results are not surprising, given that the original three Fama-French factors are often called “risk premiums.” The tough times of a recession are typically when investors flee from risky stocks—especially the riskiest beaten down names. Conversely, investors seek out quality companies with good financial health. This helps explain the better returns of the profitability and conservative investment factors during recessions.

Timing Matters

Given that we have entered a recession, should investors cut their equity allocation? Or should they move exclusively to larger stocks with good company financial health? The answer to both questions is no, because those moves present their own risks.

Factor performance can change dramatically during the run up to a recession and in the subsequent recovery. We see evidence of these shifts in the final two rows of our chart, which give factor returns before and after recessions. There is no standard definition for these periods, so for consistency and convenience we have chosen 12 months[2].

Periods before a recession are often marked by euphoria: The Roaring 20’s, the tech bubble of the 1990’s, and the period before the 2008 Financial Crisis are well-known examples. Such an environment is particularly reflected in the strong returns for momentum, as stocks that have done well continue their positive run.

Periods following recessions are often filled with cautious optimism and increased risk appetite. This is when the small and value segments typically put in their strongest performance, reversing their recession blues. Investors who try to time the market risk missing out on these very substantial gains. It’s not just when you get out, but also when you get back in that matters.

One recent example is that when the impact of COVID-19 became clear, the market sold off rapidly. It then rebounded in anticipation that the unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus will moderate the economic damage. Investors who abandoned stocks in anticipation of a recession may well have captured all the downside but missed the subsequent rally.

Key Takeaways

If timing recessions is hard and picking which factors might perform best even harder still, what can investors do? They can fall back on the principle of diversification. We recommend assembling portfolios with broad exposure across factors. As seen in the top row of the chart above, all of the factors discussed in this article have worked over long periods. While they usually don’t all work at the same time, when one is lagging, others often do well.

We also warn against making dramatic changes to portfolios simply because we are in a recession. These moves are potentially expensive in terms of trading costs and the substantial risks of not getting the timing exactly right. The run up to the current recession saw smaller and value stocks lag by historic amounts. If history is a guide, we expect the fortunes of these factors reverse as the current market cycle runs its course. We don’t know when that turning point will come, but when it does, we believe that investors who’ve maintained a diversified portfolio with broad factor exposure will be rewarded for their discipline.

Bridgeway Capital Management is an Associate Member of TEXPERS. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily Bridgeway Capital Management nor TEXPERS.

References

[1]

Recessions are defined by NBER. About 18% of the full period months and 12% of

the months since July 1963 are in recessions. The remaining months are not in

recessions.

[2] In two instances recessions were less than 24 months apart, so some months were within 12 months of both the prior and next recessions. To give each month a unique classification, we simply divided the intervening time period in half. The before and after recession periods in those cases had less than 12 months.

About the Authors

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Sportswear: Sweet Success Amid COVID-19?

As a discretionary good, sportswear may seem an unlikely

winner in the wake of COVID-19. But the category—which includes athletic

apparel and footwear—has some unique characteristics that make us think it will

emerge just fine. In fact, for stronger companies, we believe COVID-19 will be

an accelerant as the companies leverage their connections with consumers and

drive business through more profitable channels.

A Long Runway for Growth

The total addressable market (TAM) in the sportswear space is estimated at $472 billion globally.

WHAT IT MEANS: Total addressable market is a term that is typically used to reference the revenue opportunity available for a product or service.

At William Blair Investment Management, while apparel and footwear is a low-growth category overall, we have seen sportswear take increasing share over time. Sportswear increased from about 18% of the apparel category in 2007 to almost 26% in 2019.

In fact, sportswear has shown a 6.5% compound annual

growth rate (CAGR) over the past five years, one-and-a-half times that of the

apparel market

We believe this trend will continue, driven in part by a

growing middle class around the world. Per capita sportswear spending in

emerging markets, particularly China, is one-tenth that of the United States,

and has plenty of room to grow.

Economic Cycles: Mostly Background Noise

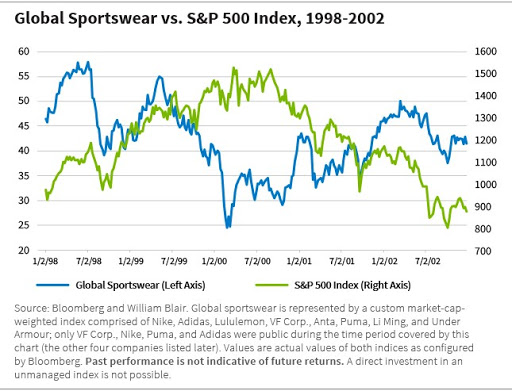

The sector’s behavior in response to economic cycles has

been mixed. While there is an impact from the economic backdrop, there are many

times that results have been detached from the economic cycle.

For example, sportswear growth peaked in 1995 and

decelerated through 1999, leading the stocks to underperform the broader

market. After bottoming in 1999, sportswear started a five-year growth

acceleration, leading to strong stock performance.

This is exactly the opposite of what the broader market

was doing: The market peaked in 2000, and growth slowed as the U.S. economy

went into a recession in March 2001.

As the chart below shows, the S&P 500 Index peaked at

roughly the same time sportswear bottomed, presenting a prominent case for how

sportswear performance has detached from the economic backdrop at times.

WHAT IT MEANS: The S&P 500 is a stock market index that measures the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the U.S.

This was also apparent after the 9/11 attacks,

where we saw sportswear quickly recover despite continued weakness in the

broader market.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

We saw more economic sensitivity

during the global financial crisis (GFC). Both the S&P 500 Index and

sportswear companies peaked around the same time, within two to three months of

each other.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

However, sportswear fundamentals

were fairly resilient. Revenues across the group declined 3% in 2009 and

earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) were down 35%, but there was a strong

rebound in 2010. While sportswear fundamentals recovered within five to seven

quarters, sportswear stocks surpassed prior peaks within a year of

bottoming—much faster than the market, due to clear visibility and robust

growth.

The key takeaway: economic cycles

matter, but they have not been as impactful as we might think they would be. We

are seeing a number of sportswear companies perform outside of the economic

cycle.

Product Cycles: Critical in the Near and Medium Term

To understand the sportswear

space, one must appreciate product cycles. While sportswear companies are not

high-fashion companies, there is a fashion element to their success, and they

need to remain on trend.

WHAT IT MEANS: A product cycle is the length of time a product is introduced to consumers into the market until it's removed from the shelves

The chart below illustrates how

three key sportswear companies performed in past product cycles.

|

| Click chart to enlarge. |

A running-related product cycle

started in the mid-2000s. It was interrupted somewhat by the GFC, but then came

back with a vengeance. This is when we saw the Nike Free and Vibram Five

Fingers products take off.

Sportswear Company 1 in the chart

above was well positioned for this cycle; Sportswear Company 3 was not. As a

result, Sportswear Company 1 outperformed Sportswear Company 3 significantly

from 2012 to 2015.

Then, from 2015 to 2018, retro

sportswear came into fashion. Sportswear Company 1 continued to push the

running platform while Sportswear Company 3 was on trend for retro. Guess which

outperformed?

We are now in a new product cycle

that we call high fashion and collaborations. Brands are collaborating with

different designers and luxury houses (Kanye West, Selena Gomez, Beyoncé, Dior,

and Off-White to name just a few), and new product releases are coming out

monthly if not weekly. Most leading brands are participating successfully in

this trend.

There are two key takeaways.

First, the category has a degree of fashion risk (such as the move away from

technical performance and athletic functionality), although it is less

pronounced than in luxury or casual wear.

Second, once we identify companies

that we believe have strong brand equity and solid management teams, we need to

make sure we are patient, because even the best will potentially miss a trend

and have a period of underperformance relative to peers.

Investment Opportunities

Over time we have seen brands

rationalize their supply chains, allocating more orders to what we would call

key manufacturing partners. We view key suppliers as strategic partners and

more akin to internal manufacturing than external. A single supplier, for

example, manufactures about one-sixth of Nike’s shoes globally.

We also see this happening on the

distribution side. Brands are culling undifferentiated wholesalers and

diverting more in-demand products to strategic retail partners. We view these

retail partners as part of a brand’s direct-to-consumer efforts more than

wholesale.

The return on invested capital

(ROIC) for these strategic partners is typically fairly robust and at times has

exceeded the brands’ ROIC, indicating that there is substantial value creation

throughout the entire value chain.

WHAT IT MEANS: Return on invested capital is a calculation used to assess a company's efficiency at allocating the capital under its control to profitable investments. The return on invested capital ratio gives a sense of how well a company uses its money to generate profits.

On that note, we see a long runway

for brands to shift sales from the wholesale channel (70% of Nike’s and

Adidas’s business) to the direct-to-consumer (DTC) channel, which includes

their own retail footprints and e-commerce operations.

WHAT IT MEANS: Direct-to-consumer is the selling of products directly to customers, bypassing any third-party retailers, wholesalers, or any other middlemen.

We believe the big brands have the

potential to reach about 50% DTC penetration in the next 10 years, and perhaps

even higher over the long term. Some estimates place DTC at 70% of the sales

mix.

While brands do not provide the

profitability difference between the two channels, we estimate that DTC

generates double the revenue and EBIT dollars of wholesale, underscoring just

how accretive the mix shift from wholesale to DTC is.

WHAT IT MEANS: EBIT stands for earnings before interest and taxes, and is a company's net income before income tax expense and interest expenses are deducted.

Sportswear in the Wake of COVID-19

We have long identified health and wellness as a structural theme driven by consumers being increasingly concerned by the connection between their lifestyle (physical activity and food consumption) and their overall health.

COVID-19 and the potential health

risks have intensified the desire to eat better, live better, and feel better.

We believe sportswear is well positioned to benefit from this as consumers

express this desire through active lifestyles.

While we believe the long-term

view for sportswear remains positive, COVID-19 has presented an unprecedented

situation resulting in a coordinated global retail shutdown. The ensuing

consumer weakness (such as unemployment), combined with a broader apparel and

footwear inventory glut, will likely hurt discretionary spending overall.

This will undoubtedly depress

near-term sales and margins as sportswear companies adjust to overall market

conditions.

Despite these challenges,

sportswear appears to be a resilient category in the midst of COVID-19, and not

just because the pandemic appears to have intensified consumers’ desire to

focus on their health and wellness.

Sportswear companies, over the

past few years, have woven digital engagement into their DNA. Their ability to

speak directly to an audience without a physical footprint, amplify their

messaging, and drive engagement has allowed them to drastically accelerate

online sales during the lockdown.

Multiple brands, for example, have

reported triple-digit e-commerce growth in China throughout the lockdown,

helping them offset lost brick-and-mortar retail sales.

While the pace of the recovery

varies by brand and region, we are encouraged by what we are seeing and

anticipate that sportswear sales will be one of the fastest discretionary

categories to recover, as we have seen in prior downturns. As retail conditions

normalize globally, so will sportswear sales.

After all, the category has a long track record of value creation over the past 30 years. We have every reason to believe this will continue over the long term.